Who dat in Lower Nine? The Role of Voluntariness in the Aftermath of Hurricane Katrina

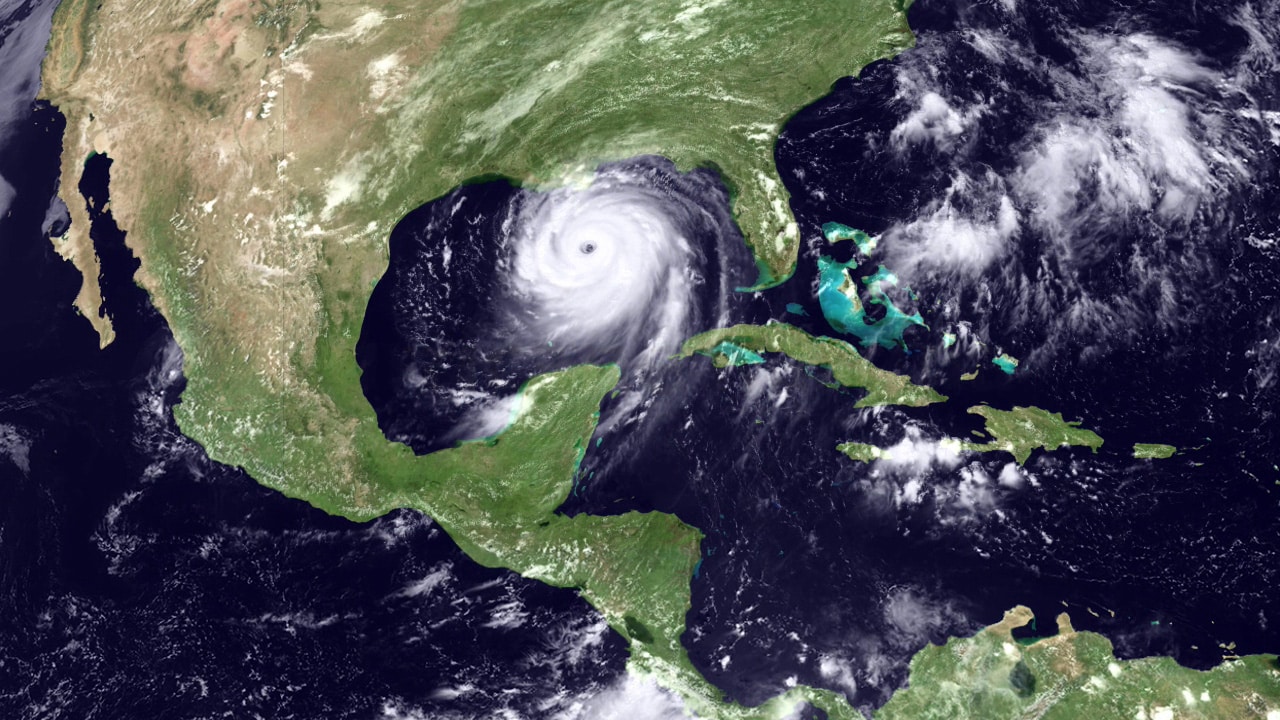

“South Louisiana is probably the most vulnerable place to climate change in the United States,” (Louisiana Climate Action Plan, 2021) as future hurricanes are likely to be severe, rising seas threaten the entire Gulf Coast, and low-lying, low-income areas with neglected infrastructure are prone to major flooding (IPCC Sixth Assessment Report, 2022). This fatal mix of looming man-made and natural disasters poses a particular risk to the vulnerable city of New Orleans. The 17th anniversary of Hurricane Katrina seems like an opportune moment for a final wake-up call. This post Who Dat in Lower Nine? will therefore take a closer look at NOLA, more specifically the Lower Ninth Ward (Lower Nine), Katrina’s aftermath and the role voluntariness played in it.

Lower Nine, a post-Katrina hotspot and New Orleanian cultural treasure, is part of the historically neglected 9th Ward with a rich cultural and racial heritage – home to Fats Domino as well as the majority of Mardi Gras Indians. The predominantly Black ward is characterized by many small businesses, barber and beauty shops, corner grocery stores, eating spots, gas stations, day care centers, and churches. However, the Lower Ninth Ward has also long suffered economic hardship, as 40% of its residents live below the poverty line, twice the statewide rate. The neighborhood is a prime example of the concentrated poverty in the city, which is continuously reinforced by its geographical isolation. The ward is bordered to the west by the Industrial Canal, to the north by the Southern Railway railroad and the Florida Avenue Canal, to the east by the parish line, and to the south by the Mississippi River, which also makes it highly prone to flooding. Thus, on August 29, 2005, Hurricane Katrina hit Lower Nine particularly hard as a result of levee failure at the district’s boundary. Nearly 77% of New Orleans and all of the Lower Ninth Ward ended up under water due to the breaching of floodwalls and levees, which caused damage to 372,000 homes and led to the displacement of at least 800,000 people.

For many, both leaving and returning to the city was a privilege rather than a voluntary choice. Mobility in and around New Orleans continued to be shaped by both race and water: Blacks made up 24% of carless households compared to 7% of whites who lacked a car in the counties most affected by the hurricane. This spatial and social immobility of many Lower Nine inhabitants mirrors the field of constraints that severely restricted their capacity to act. Having an acceptable alternative to a specific action option is often identified as a key criterion for voluntariness. Thus, Secretary of Homeland Security Michael Chertoff’s statement seemed in every sense out of place: “Local and state officials called for a mandatory evacuation. Some people chose not to obey that order. That was a mistake on their part.” Did carless people in the Lower Nine, with no other infrastructural access available to them in many cases, truly have the option of leaving the ward? What is perceived as an acceptable alternative for some depends on the preconditions for action in a specific situation for others.

When it thunders and lightning and the wind begins to blow

When it thunders and lightning and the wind begins to blow

There’s thousands of people ain’t got no place to go

Bessie Smith, “Back Water Blues”, 1927

Place Matters: Belonging and Voluntary Homecoming

Moreover, the people of NOLA and especially of Lower Nine understood themselves in terms of place. As the saying goes: “There’s no place like New Orleans.” Nearly nine out of ten African Americans who lived in New Orleans before the flood had been born in the city and Lower Nine had one of the highest multi-generational rates of black home ownership in the U.S. This sense of place motivated people to return to the city, as it offered attachment, identity but also dependence. These criteria influenced the decision-making of many inhabitants and thereby their “voluntary homecoming.” Voluntary decision-making and acting are integrated into a multifaceted set of conditions and are therefore situational. The situationally specific preconditions for and consequences of a choice or an action have a great influence on the degree to which we perceive them as voluntary. But can we still refer to voluntary decision-making if a person’s choices are deeply constrained by their cultural heritage as well as racial discrimination, or if their strong attachment to a specific place means that they deem no alternatives acceptable? The ability to leave as well as to return was extremely limited for people in the Lower Ninth Ward. In addition, those residents who wanted to come back home faced various challenges.

Whereas many communities in NOLA benefited from the signaling effects of returning “first movers” such as schools, churches, and key businesses, residents of the Lower Ninth Ward still had no certifiable drinking water, there was limited street lighting and supermarket access within the ward until 2009, and no school had reopened there before 2011. Thus, only 9.9 percent of the Lower Ninth Ward’s population had returned by 2009. Further, the mismanagement of governmental funds and aid hit Lower Nine particularly hard. The gap between the cost of repair and the amount of insurance and Road Home coverage was under 31,000 USD for white people, over 39,000 USD for African Americans, and more than 75,000 USD in the Lower Ninth Ward. Lower Nine was in desperate need of help, but President George W. Bush’s words soon rang hollow: “I […] offer this pledge of the American people: Throughout the area hit by the hurricane, we will do what it takes, we will stay as long as it takes, to help citizens rebuild their communities and their lives.” His speech did not mirror the reality of government support for New Orleans in 2005 or at any time up to today. Author, academic and former Canadian politician Michael Ignatieff called it “[t]he Broken Contract,” the government’s failure to fulfill its duties of care to the people, so crucial in a democratic society, by helping them to protect their families and possessions from forces beyond their control. Thus, the people of the “orphan neighborhood” started to take care of themselves with the help of volunteers and lived together through a civil society vacuum caused by “failure of government at all levels to plan, prepare for, and respond aggressively to the storm” (Homeland Security, 2006).

Volunteering as an Ideal of Citizenship in American Liberal Society

According to political philosopher Michael Sandel (1996), voluntary action is often expected to fill the gaps in public provision and citizenship is therefore often understood as a responsibility to honor contractual relationships to others and to the state. However, this expected form of voluntary commitment in the absence of government leads to the exclusion of certain societal groups, as in the case of Lower Nine. Prior disaster experiences suggest that African Americans are particularly vulnerable to housing damage and have more difficulty rebuilding afterwards since recovery and reconstruction after a disaster are essentially a private rather than governmental matter. Marginalized neighborhoods are excluded from the regime of choice and do not benefit from the social politics of solidarity; instead, they are allocated to a range of new para-governmental agencies, such as voluntary organizations. Thus, voluntary action is largely defined by the constraints of class and race. While liberal democracies are governed through voluntariness and demand “active citizens” that voluntarily participate, organize, and commit to public life, they are simultaneously exclusionary as they deny certain groups of people recognition of their capacity for active citizenship and voluntary action. Such marginalized groups then have to fight their exclusion as well as the immobility characteristic of places such as the Lower Ninth Ward.

Voluntary associations and small government are in fact an American specialty, as Alexis de Tocqueville already stated in his 1840 classic Democracy in America: “These Americans are peculiar. If in a local community a citizen becomes aware of a human need, which is not met, he thereupon discusses the situation with his neighbors. Suddenly, a committee is formed. […] These citizens perform these functions without a single reference to any bureaucracy or any official agency.” Participation in voluntary associations has always been believed to be fundamental to American public life; in line with this, thousands of volunteers gathered in the direct aftermath of Katrina and are still gathering today to support the residents of the Lower Ninth Ward. Most of the community organizations in the ward have developed with the help of coalitions of people from within and outside Lower Nine and are small, unincorporated non-profit organizations such as lowernine.org or Common Ground Relief. Volunteering is often regarded as an active form of citizenship that liberal-democratic societies seem to expect; nevertheless, it is a privilege to choose to volunteer and not to depend on it. In the case of Lower Nine, the devastation and loss were too extreme for private projects to truly rebuild the ward. Even disaster researcher Charles Fritz’s acclaimed concept of positive disaster experiences applies mostly to those who could interact freely and volunteer by choice rather than those whose houses were destroyed and who had no real means of saving them. The Katrina-related flooding has “forever altered the fabric of the historic Lower Ninth Ward” as underlined by a historical marker near the new Industrial Canal Flood Wall, a constant reminder of why this event occurred and of what was tragically lost. It is now up to us to better protect each other, whether out of self-interest or solidarity. As the recent flooding in Kentucky has shown, we are running out of time to respond appropriately to catastrophic climate change or to act voluntarily to avert it.

Suggested Citation: Herzan, Pia: “Who dat in Lower Nine? The Role of Voluntariness in the Aftermath of Hurricane Katrina”, Voluntariness: History – Society – Theory, August 2022, https://www.voluntariness.org/who-dat-in-lower-nine/.