The Citizens’ Forum on the DDR-Neuererbewegung

“You’re too late!” declared an elderly gentleman at the other end of one of the three large tables that had been set up in the Ehrhardt Room of the Automobile Welt Eisenach museum on the occasion of our <a href="http://“You’re too late!” declared an elderly gentleman at the other end of one of the three large tables that had been set up in the Ehrhardt Room of the Automobile Welt Eisenach museum on the occasion of our Citizens’ Forum on the DDR-Neuererbewegung, held on September 30, 2022. What he meant was that many former employees of GDR enterprises who would have had plenty to say about the Neuererbewegung, the GDR’s workplace inventor and suggestion scheme known as the “Neuerer- und Rationalisatorenbewegung,” were getting on in years or already deceased. Most of our fourteen guests were in fact of advanced retirement age, but they did not miss the opportunity to share their memories with us. In doing so, they made a valuable contribution to the research project “Voluntariness and Dictatorship: Voluntary Participation in the ‘Neuererwesen’ of the German Democratic Republic.” In cooperation with the Oral History Research Center at the University of Erfurt, the personal experiences of former “Neuerer” enabled us to contextualize the insights we had gleaned from the archive of the state-owned Automobilwerk Eisenach (VEB AWE), the Thuringian Land Archive, and the Federal Archive in Berlin. At the same time, the event served to bolster dialogue between civil society and academia by publicly presenting and discussing our research project, approach, questions and ideas.”>Citizens’ Forum on the DDR-Neuererbewegung, held on September 30, 2022. What he meant was that many former employees of GDR enterprises who would have had plenty to say about the Neuererbewegung, the GDR’s workplace inventor and suggestion scheme known as the “Neuerer- und Rationalisatorenbewegung,” were getting on in years or already deceased. Most of our fourteen guests were in fact of advanced retirement age, but they did not miss the opportunity to share their memories with us. In doing so, they made a valuable contribution to the research project “Voluntariness and Dictatorship: Voluntary Participation in the ‘Neuererwesen’ of the German Democratic Republic.” In cooperation with the Oral History Research Center at the University of Erfurt, the personal experiences of former “Neuerer” enabled us to contextualize the insights we had gleaned from the archive of the state-owned Automobilwerk Eisenach (VEB AWE), the Thuringian Land Archive, and the Federal Archive in Berlin. At the same time, the event served to bolster dialogue between civil society and academia by publicly presenting and discussing our research project, approach, questions and ideas.

What Did It Mean to Be a Neuerer? Tracking Down Lived Experience Through Oral History

Our core interest was in our guests’ memories, interpretations, and narratives. The oral history method always entails an interplay between the past and the present from which this past is recounted and reflected on. Sharing memories does not mean perfectly reproducing lived events, but rather perceiving them as a construction shaped by later occurrences, experiences, reflections and repeated telling. This makes it vital to include in our analysis the time span between the lived event and the present in which it is recounted. These two trajectories are also relevant to the study of voluntariness, especially with respect to its ethical dimension and associated moral attributions.

What was regarded until the upheaval of 1989–90 as a voluntary commitment and innovative achievement worthy of accolade was quick to be interpreted after this watershed as compliant support for a dictatorial regime. Interestingly enough, our guests did not discuss this presumed turnaround. For them, submitting proposed innovations or working on so-called Neuerervereinbarungen, that is, “carrying out innovation tasks together as a collective,” does not mean “participation supportive of the regime.” In the 1990s, when conducting and analyzing interviews with contemporary witnesses about the GDR era, it was crucial to bear in mind interviewees’ tendency to relativize their cooperation with state organizations due to a certain pressure to justify themselves. But this is far less of an issue today. This is due, first, to the fact that most former GDR citizens are now in their twilight years and no longer have to fear professional consequences. Second, public discourse has changed since the 1990s such that the social engagement of the time can no longer be dismissed one-dimensionally as evidence of loyalty to the regime or the like. At least in recent historical research on the GDR, analytical lenses such as the category of Eigen-Sinn have made for more nuanced interpretive approaches.

Between Plan Fulfillment and Group Dynamics

In order to find out which periods of time and events were particularly formative for our guests, Agnès Arp, Alexandra Petri (both of OHF), and I intervened as little as possible in the conversation. When the event got underway, we allowed our guests to freely choose their seats at the tables (featuring writing materials and snacks) and thus their conversation partners. It may come as little surprise that those who already knew each other or who spontaneously forged a connection sat together. Thus, the draftsmen and engineers of VEB AWE formed a group, former office workers occupied one of the tables, and mostly skilled workers from the sphere of production struck up a conversation at a third table. The office workers talked about how they had dealt with the key figures specified in the economic plans and told of cases in which a degree of creative license had come into play to bring the accounts into line with state guidelines. A former auditor reported that financial statements relating to the targets set for the Neuererbewegung were often embellished because too few proposals had been submitted and the existing ones were entered into the accounts several times over. Jokes were made about the discrepancy between aspirations and reality under socialism; after all, no one in the group had experienced personal cuts in income at the hands of the regime—and none of them counted themselves among the so-called “losers of reunification.”

A different situation pertained among the skilled workers, who saw the Neuererbewegung purely as a “necessary evil” under a regime that had offered them no opportunities for professional or personal advancement. There had not been “a single honest day,” one person stated disgruntledly. Ultimately, they had been united by scarcity, as everyone around the table agreed. The engineers, meanwhile, recounted various proposals and innovations they had put forward to enhance car production in Eisenach. Due to a lack of materials and tooling technology, however, many of these forward-looking ideas went unused and in some cases were even rejected by ministerial decree. It was only after 1990, when the Eisenach plant was taken over by Opel, that the engineers’ ideas were listened to, the West German company having established its own suggestion scheme. One of the former engineers proudly reported that, with the help of suggestions from former GDR cadres, the Opel site in Eisenach was able to chalk up the best production figures in Europe in the early 1990s. The belated recognition of their expertise seemed to give these men a kind of satisfaction; the socialist regime had curtailed their creativity and enthusiasm for various reasons and thus deeply offended them in relation to their self-image as engineers.

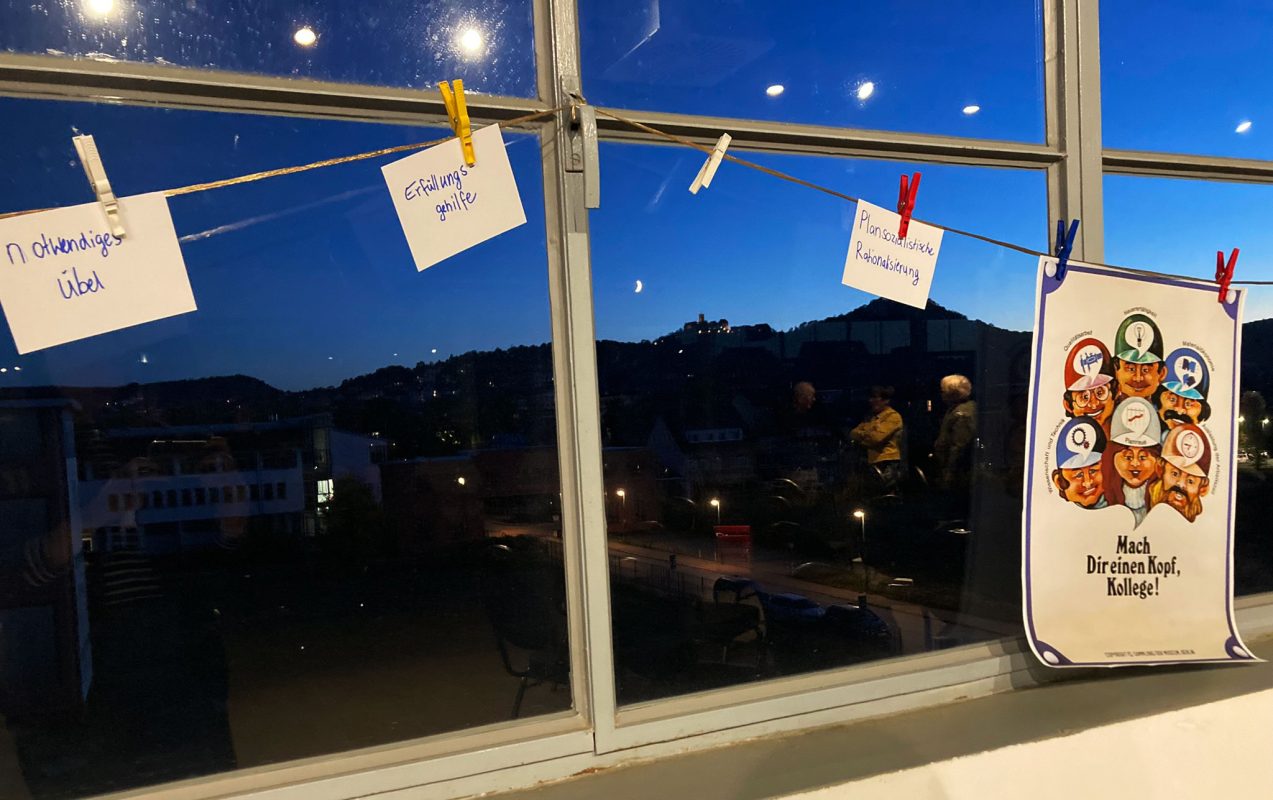

After a well-deserved break, we reconvened in a large group made up of all the participants, moderated by Agnès Arp, to discuss the various memories and perspectives together. Interestingly, it turned out that the quite different experiences and events were by no means mutually exclusive, let alone a trigger for conflict due to differences of opinion. An attentive and sympathetic atmosphere prevailed. An individual’s employment relationship and professional self-image, as well as the resources and opportunities available in this context, were often decisive to their experiences with the Neuererbewegung. This was also evident in the way stories were told. The engineers, for example, gave detailed accounts of new parts intended to reduce fuel consumption and exhaust emissions while maintaining engine performance. In contrast, one skilled worker stated that he enjoyed working on new “Neuerervereinbarungen”, as a team because it was fun to fiddle about together and then “celebrate” the bonus. “Nobody got rich,” the elderly man told us. Before we closed the discussion around 7 p.m., we asked the guests how they would describe the Neuererbewegung in a single phrase. The answers were varied and complementary: “accomplice,” “necessary evil,” “opportunity to make money,” “made work easier,” “lost opportunity,” “means to an end,” “improvement,” “attempt at something new,” “plan fulfillment,” “plan of socialist rationalization,” and “general necessity.” There is little echo here of GDR propaganda, which extolled the Neuererbewegung as a “cadre forge” for the socialist leadership and a mainstay of German-Soviet solidarity.

At this event, it became clear that these contemporary witnesses had highly idiosyncratic motives for submitting and working on innovator proposals and tasks that were only very remotely connected to the claims propagated by the movement, if at all. They perceived their participation within the organization primarily as an opportunity for additional income in the form of “Neuerervergütung,” used the associated activities for professional development and creativity, or even viewed them as a shared form of leisure. Thirty-three years after the fall of the Berlin Wall, our guests spoke openly about their voluntary involvement in a mass political organization, without describing themselves as convinced socialists. The reality and circumstances of voluntariness were complex, reminding us of our ongoing task to perceive, analyze, and contextualize the varied range of voices on GDR history. This makes it essential to enter into conversation with the protagonists, to critically analyze their memory-based accounts and relate them to the archival sources. It’s crucial that we listen before their voices fall silent.

Suggested Citation: Kiesel, Elena M. E.: “Voluntariness As a ‘Necessary Evil’? The Citizens’ Forum on the DDR-Neuererbewegung”, Voluntariness: History – Society – Theory, January 2023, https://www.voluntariness.org/voluntariness-as-a-necessary-evil/