© lithography by Ch. Reisser & W. Werthner, WFRG archives, photograph by Alexander Obermüller

Vienna Calling: Volunteer Emergency Medical Aid at the Turn of the Century

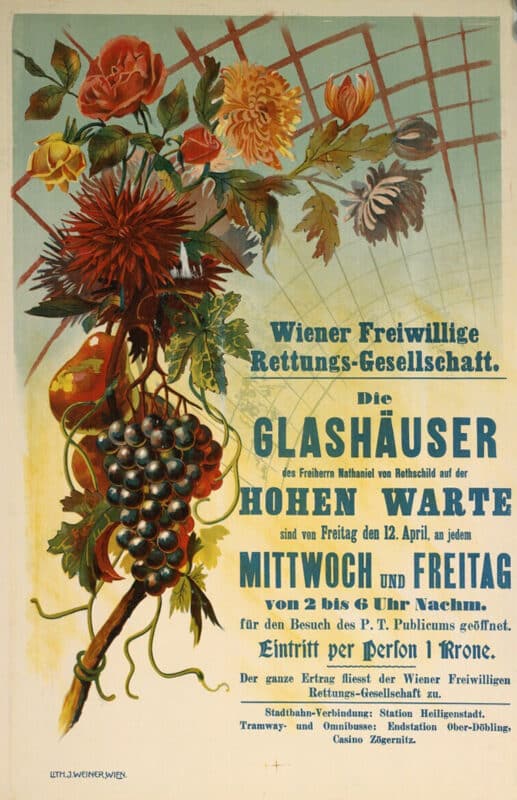

In October 1886, Vienna’s Voluntary Ambulance Association (VVAA, Wiener Freiwillige Rettungsgesellschaft) sold colorful lottery tickets to its supporters. The proceeds funded VVAA’s day-to-day operations, including the provision of emergency medical care and transport for the sick and poor. Those activities fell under the organization’s first aid-branch, which was represented on the lower right corner of the lottery ticket by stretchers and rescue equipment. VVAA’s other two branches—water rescue and firefighting—were also represented on the tickets, by first responders using a boat to rescue an unconscious woman from a river and a firefighter battling a blaze with a firehose while carrying a child. The depictions stressed the multiple ways in which VVAA volunteers improved lives by protecting health and safety. By buying a lottery ticket, one could support a good cause.

Today the city of Vienna employs over 700 paramedics, yet volunteer first responders still supplement city services. Beyond large cities, emergency medical care and firefighting still rest in the hands of volunteers. According to recent statistics, in 2022, 22 percent of all those who volunteered in an institutionalized setting were engaged in providing first response emergency medical care. Their numbers total 366,000, and they are overwhelmingly (80%) male, performing 1.5 million hours of unpaid labor in Austria each week. By going back to the late nineteenth century, this article traces the history of this reliance on volunteers. First, it highlights the VVAA founders’ struggle to raise money, acquire equipment and sign up volunteers to serve the city’s sick and poor. Second, it considers why VVAA volunteers were predominantly middle class. Finally, the article examines the notion that volunteering necessitates unpaid labor and asks if donating can also be viewed as volunteering.

Volunteering: A Middle-Class Sport?

When Moravian nobleman and physician Jaromír Mundy (1822–1894) founded the VVAA in 1881, he envisioned the organization as a benevolent institution. Mundy, who had taken an active role in founding the Red Cross movement, saw delivering first aid as his calling. Yet, right from the start, the VVAA’s financial situation was precarious. Mundy solicited wealthy aristocrats for contributions. They included Hans Wilczek who donated 5000 florins. Some of the first horse-drawn carriages that the VVAA used to transport patients had also been donated. Selling lottery tickets and soliciting donations, two activities spearheaded by prominent women including the “First Lady of Charity” Pauline Metternich Sandor, were key to keeping the organization afloat.

Financial struggles aside, by 1886, the VVAA had become a mainstay of Vienna’s sprawling philanthropic scene. Organizations such as the Poliklinik, which had opened its doors in 1872, served a similar constituency, caring for the poor who would have otherwise gone without health care. The VVAA boasted between 700 and 900 volunteers with 250 firefighters and 160 members of rowing clubs lending their time, strength, skills, and expertise. Between 160 and 300 medical students had also signed up, as had several physicians (160–180).

Some of the VVAA’s earliest regulations stipulated that only men who could freely dispose of their time—those who were not salaried personnel—could volunteer. VVAA regulations therefore excluded workers who sold their labor for meager wages. Consequently, volunteers mostly hailed from the middle-class. Experienced physicians, medical students, and lay first responders who had been trained in the VVAA’s own school made up the bulk of the VVAA’s first aid-branch. These rules created a homosocial environment wherein military organizing principles, ideals of heroic masculinity, and medical prowess coalesced.

© unknown photographer, ca. 1860, Wien Museum Inv.-Nr. 76553/27

The VVAA’s water rescue-branch brought together members of various recreational rowing clubs including the “First Vienna Rowing Club Lia” and others with names like “Donauhort”, “Pirat”, and “Donaubund”. When joining the VVAA, they pledged to crew two rescue boats during frequently recurring floods. The clubs also donated the proceeds of (some of their) charity events. Lists of “Lia”-members who signed up for the VVAA roster confirm that volunteering—and recreational rowing for that matter—were activities for the middle and upper classes. Merchants, engineers, clerks, and bookkeepers were the ones who regularly plied Vienna’s water ways.

The makeup of VVAA’s firefighting branch presented an exception. Across East-Central Europe volunteer fire brigades were organized as self-governed neighborhood associations that also offered camaraderie. In Vienna, fire brigades included factory workers, brick layers, fitters, and weavers from working class districts such as Simmering, Ottakring, and Floridsdorf. Their employers had enlisted them to mitigate fire risks at factories including the “Maschinen- und Waggonbaufabriks-Actiengesellschaft” and the Austrian “Jutespinnerei und Weberei”. Some of those workers also volunteered for the VVAA. Working class firefighters’ volunteerism then had a markedly different character since their livelihoods depended on them protecting their workplaces. Coercion from employers might have also played a role.

Does Volunteer Work Mean Unpaid Labor?

© public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

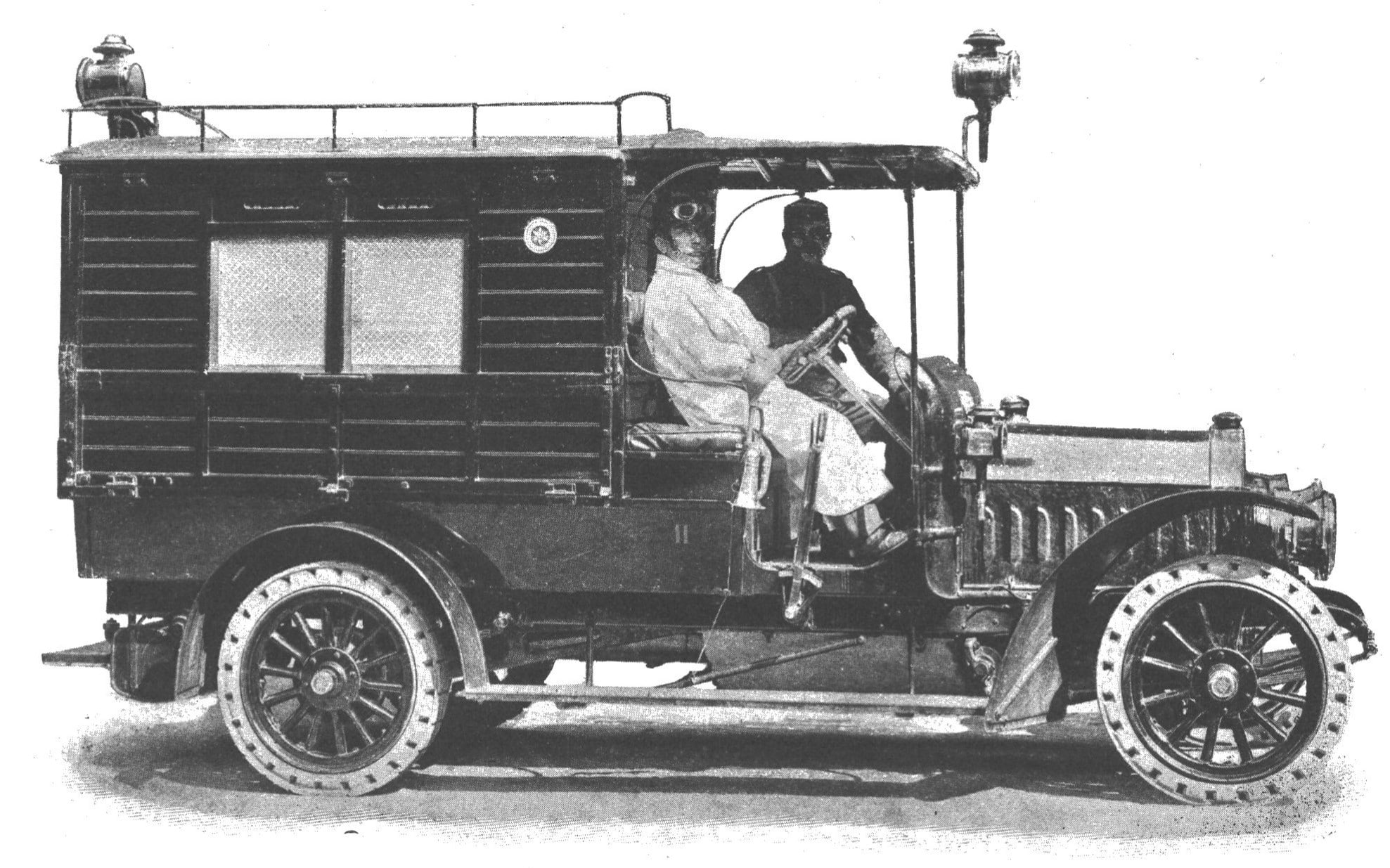

Considering Vienna’s population of close to two million, an organization that enlists roughly 500 volunteers to deliver first aid—and conveniently adds existing fire brigades and rowing clubs to its roster—might not appear impressive. Yet emergency medical care that VVAA staff provided represented one of the earliest efforts to organize professional ambulance services, on a volunteer basis no less. Other organizations, such as the St. John’s Ambulance Association in England, had begun disseminating knowledge about first aid in the late 1870s. The VVAA, by contrast, brought emergency medical care directly to its patients. In 1886, members of the first aid-branch had responded to 650 “sudden illnesses”, treated close to 1,500 injuries, and transported more than 2,100 patients, amounting to a total of over 4,250 calls for service. By 1894, the VVAA would double those numbers. However, that same year, the organization also switched to salaried personnel by rescinding a rule that barred payment to volunteers.

Today, a person who volunteers rarely expects payment. Those who do are generally thought of as employees of a non-profit organization. Public perception of the VVAA however did not change when the organization started to hire a staff that included eleven physicians, three clerks, ten paramedics, and five coachmen. Medical students continued to supplement the VVAA’s ranks, suggesting that volunteering with the VVAA had standing in their education. Some of them, after finishing their studies, even signed on as physicians. What does it mean that an organization that proudly carried the word “voluntary” in its name switched to salaried personnel?

First, VVAA’s turn to a paid staff did not change its reliance on a volunteer-based financing model. The organization still depended on membership fees, donations, charity events, and lottery ticket sales. That is how most Viennese supported the VVAA, regardless of whether the organization relied on volunteers or salaried personnel. Meeting minutes document attempts to secure funding from the city of Vienna, but city administrators wanted representation on VVAA’s board in return. Some inside the organization were reluctant to subject it to the outside influence of government funding. They argued for a reliance on private individual donations to maintain the organization’s independence. Furthermore, aristocratic and bourgeois liberal reformers including Mundy saw self-reliance as a key aspect of VVAA’s humanitarian work. Asking the state to step in ran counter to their understanding of civic-minded and religiously infused voluntary benevolence.

Second, by paying its personnel, the VVAA was appeasing some critics from the medical establishment. Status conscious physicians had voiced concerns that colleagues who volunteered with the VVAA and provided medical services for free might be siphoning off their business. It was a charge that the Poliklinik had also faced. One report in the Morgen-Post encapsulates the stakes of the debate. The article highlighted the conflict between the VVAA and physicians who provided out-patient care. Dubbing this conflict “Rettungs-Concurrenz”, the article speculated that competition for patients might lead to VVAA its competitors literally carving up and carrying away half of their “prey”. By 1894, this conflict seemed to have been settled by VVAA’s establishment of a paid, stable staff.

© public domain, collection of Albertina, via Wikimedia Commons

The history of volunteer ambulance services does not run in a straight line from the late nineteenth century to the present. Yet some aspects of the VVAA’s history—financial precarity, male dominance, rivalry among health care providers—reverberate today. Austria’s large volunteer sector regularly elicits praise. That emergency medical services would cease to function without the millions of volunteer hours is also acknowledged though there are few legislative attempts to remedy that vulnerability. When the public debated whether to eliminate compulsory military service, along with community service that young men can opt for instead, the threat that terminating the latter would pose to the health care system became the strongest argument for retaining both. Most men serve out their nine months of alternative community service within the health care sector e.g. with the Red Cross. After three months of training, they are certified paramedics. Many stay on after their compulsory service as volunteers, which explains the large share of male volunteers in this field. Critics regularly bemoan the lack of training Austrian paramedics receive and the exploitative nature of community service. Yet paying volunteers, some argue, would not only be financially untenable, but would also destroy the volunteer spirit. The VVAA and its history show that paid labor and the spirit of volunteerism can, in fact, coexist.

Suggested Citation: Obermüller, Alexander: “Vienna Calling. Volunteer Emergency Medical Aid at the Turn of the Century”, Voluntariness: History – Society – Theory, February 2025, https://www.voluntariness.org/vienna-calling/.